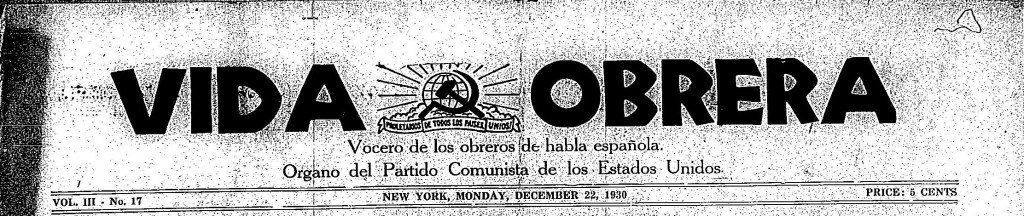

Documents from the Soviet Archives and an examination of the Vida Obrera (Workers Life) reveal a dynamic and innovative American Communist movement committed to organizing Spanish-speaking workers beginning in 1929. These initiatives coincided with the formation of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA) a dozen years after the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution; the propitiously timed campaign corresponded with the start of the Great Depression and the seemingly uncaring presidential administration of Herbert Hoover.

So begins my article, “The American Communist Party’s Spanish Bureau: Third Period Activities and Some Subsequent Impact” in the new issue of the American Communist History (Vol. 11, No. 3, 2012).

This is the first academic article to examine the early years of the Communist Party’s interest in organizing Latino workers. The underlying was possible only because of the Library of Congress’s copying of the CPUSA documents long stored in the Soviet Archives (and made available to scholars at a number of universities, such as Stanford, where I availed myself of the materials).

The Spanish Bureau documents focus on the years 1929 to 1931. They include a number of surprising insights. To begin with, the Spanish Bureau was the party’s only outreach operation organized around a shared language and not a shared ethnicity (such as Jewish) or nationality (such as being from Greece or Russia). Moreover, the original five-member Spanish Bureau did not include either a Puerto Rican or a Mexican American, a situation the party consciously rectified.

The question as to why the Communist Party began to focus on Latinos when and how they did has long been a subject of speculation because the Socialist Party, from which the CP emerged, included a number of foreign language-based fraternities, but none representing Spanish speakers.

By way of explanation, the documents point to a confluence of three interests: Latinos working among the industries targeted for unionization, an ideological affinity for the most oppressed sectors of the working class, and the belief that immigrants in the U.S. could aid the liberation struggles in their native lands.

The absence of an existing left-wing fraternal order among Latino immigrants led to the party’s putting a priority on creating Spanish-speaking lodges affiliated with the International Workers Order (IWO). Such IWO lodges were subsequently formed in New York, Philadelphia, Denver, and Los Angeles. These fraternal organizations were to assume a political importance; members shared a progressive outlook but most were not party members; they sponsored cultural activities, provided health care services, and backed candidates and issues.

The party’s political strategy was to become more sophisticated in later years. It ran Albert Moreau, an Argentine born-activist for the state Assembly in New York in 1929. In 1936, recognizing that Puerto Ricans constituted the largest (and growing) Latino group in the state, the party ran two Puerto Ricans, Felix Padilla and Jose Santiago, for the New York State Legislature.

Starting in 1937, the party backed American Labor Party–endorsed legislative candidates, helping that year to elect Assemblyman Oscar Garcia Rivera as the first Puerto Rican–elected official in the United States. Mayor La Guardia’s Fusion Party and the Republican Party also backed Rivera against a Tammany Hall Democrat.

On the labor front, the party’s extended effort to reach Latinos as part of a larger strategy to organize steelworkers in the Midwest bore little fruit, although inroads were made in the packinghouses. These efforts in the Midwest stood in marked contrast to well-known mass strikes in California agriculture and the lesser-known work among cigar makers in Florida.

The party-led Trade Union Unity League affiliate, the Tobacco Workers International Union, organized cigar workers in New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Florida. The 1931 strike in Tampa turned into a general strike in the Ybor City and West Tampa neighborhoods dominated by Cuban and Spanish cigar makers.

The 18-page article is recommended for those interested in better understanding the origins of the Latino labor left nationally and in specific communities, such as Spanish Harlem and Tampa and points west.