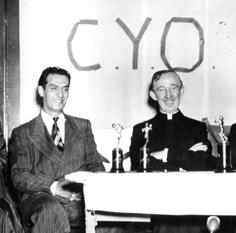

Beginning in 1947, Mexican American members of Los Angeles’ AFL International Ladies Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU) and the CIO United Steel Workers of America (USWA) became active in the newly formed Catholic Labor Institute (CLI).

The CLI was sponsored by the Archdiocese of Los Angeles during the final days of Archbishop John Cantwell, an Irish-born New Dealer.

The CLI supported organized labor in dealing with unfair employers, encouraged companies to respect the collective bargaining process, and trained Catholics to become more active in their unions.

The CLI was political on several levels.

First, it assumed controversial positions on issues of public policy. Most significantly, the CLI director, Father Thomas Coogan, used the 1947 Labor Day Mass at St. Vibiana’s Cathedral to blast the Taft-Hartley Bill, recently enacted by Congress over President Truman’s veto. He said the law “denies basic rights of workingmen.” This outraged the conservative Los Angeles Times, but provided instant credibility within the ranks of organized labor.

Second, the creation of the CLI dovetailed with the creation of the Mexican American–oriented Community Service Organization (CSO). CSO, an affiliate of Saul Alinsky’s Industrial Areas Foundation (IAF), initially focused on ameliorating neighborhood concerns, starting with the need for stop signs and stoplights. CSO also dealt with discrimination in employment and housing, as well as police abuse.

The ILGWU, USWA, and liberal labor priests served as the three organizational pillars of both CLI and CSO. In many ways, CLI and CSO represented a strategic effort by the three partners to create new progressive—but non-Communist alignment— that would strive to improve life on the job and in the community.

The liberal clergy knew that too often the Church had provided immigrants with the sacraments and charity, but had not focused enough on social justice. And within labor circles, the AFL Central Labor Council was seen as little concerned with community issues. On the other hand, the CIO Council placed a high priority on racial equity and social justice, but it was run by Phil Connelly, a Communist.

Third, priests associated with the CLI sought to influence events in the electoral arena. The Church played a major role in CSO’s voter registration drive in 1948, and in the election of founding CSO president Edward Roybal to the Los Angeles City Council in 1949.

Monsignor Thomas O’Dwyer, CLI’s patron in the chancery and in East Los Angeles, publicly endorsed Roybal. The clergy helped mobilize Latino voters.

Roybal was more than the first Mexican American on the City Council in modern times. His election also doubled the number of Catholics on that body. The other thirteen members were Anglo-Saxon Protestant. That mattered in 1947.

In 1948 the CLI opened its third labor school, the Pius XI School of Labor Relations, at St. Mary’s in Boyle Heights. It was pastored by O’Dwyer, and it became the mother church for many Eastside Spanish-speaking congregations.

The CLI became a flashpoint in the early 1950s when it took the initiative to prevent the Communist-led United Electrical, Radio & Machine Workers (UE) Local 1421 from winning a representational election at Standard Coil, a secondary parts manufacturer with a largely Latina workforce.

Standard Coil produced parts for the Sabre jet, which was then battling Soviet MIGs over Korea. This infused national security into the union election that ultimately revolved around long-established CLI-CSO-ILGWU-USWA relationships.

The labor priests convinced CSO president Tony Rios to take a leave of absence from his job as a steelworker to lead the anti-UE campaign.

(For more on this dynamic story, see “The Battle For Standard Coil: The United Electrical Workers, the Community Services Organization and the Catholic Church in Latino East Los Angeles,” in Robert Cherny, William Issel, and Kierran Walsh Taylor, eds., American Labor and the Cold War: Grassroots Politics and Postwar Political Culture [New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2004]).

The Catholic Labor Institute in Los Angeles in the late 1940s and early 1950s provided an important thread in the fabric of Latino Los Angeles that reached into the pew, on the job, and throughout the neighborhood.

Another part of CLI’s effectiveness may derive from its efforts to reach workers on a spiritual level. It invited blue-collar Catholics to see themselves in the image of a working-class Christ. Mexican Americans recited the “The Prayer of the Worker” as adopted from the Association of Catholic Trade Unionists:

The Prayer of the Worker

Lord Jesus

Carpenter of Nazareth

You are a worker as I am.

Give to me and all the workers of the world

the privilege to work as You did

so that everything we do

may be to the benefit of all our fellow man

and the greater glory of God the Father.

Thy Kingdom come

into the factories and into the shops

into our homes and into our streets.

Give us this day our daily bread.

May we receive it without envy or injustice.

To those who labor and are heavily burdened

send speedily the refreshment of Thy love.

May we never sin against Thee.

Show us Thy way to work and when it is done

may we with all our fellow-workers

rest in peace. Amen.